Jimmy Wynn passed away last night. This SABR article was written by Mark Armour in 2014.

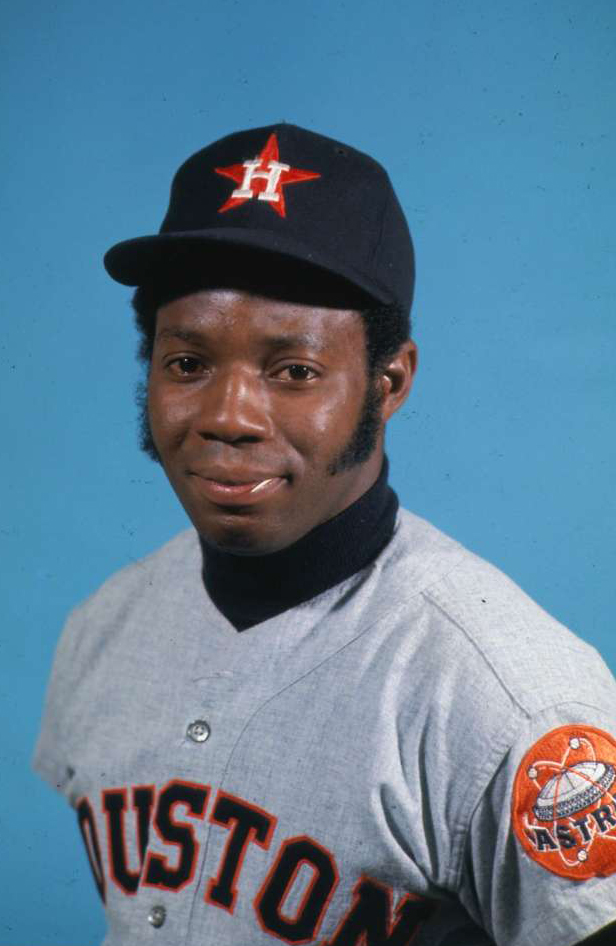

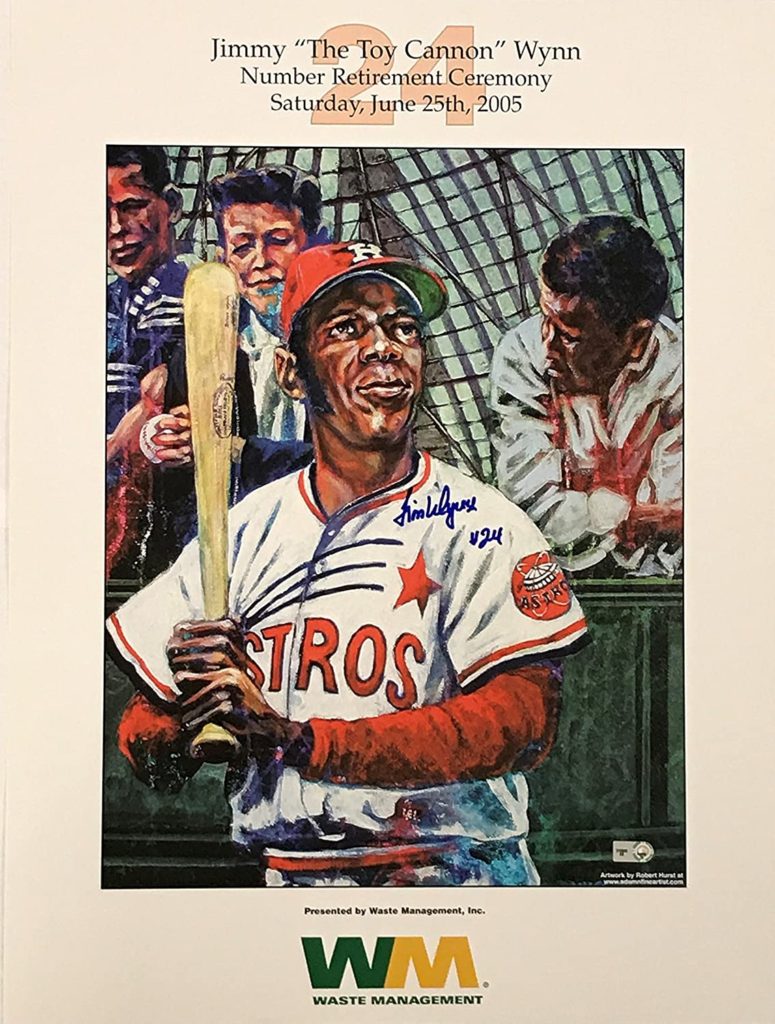

Sometime during the 1967 baseball season, Houston Chronicle sportswriter John Wilson first referred to Houston Astros’ center fielder Wynn as the “Toy Cannon.” Wynn did not like the nickname at first, believing, justifiably, that it was yet another reference to his small (5-feet-9, and a muscular 165 pounds) stature. But the name hardly poked fun – it was an extreme compliment whose second word brought to mind the damage he could do with his bat. The name fit, thought the great writer Jim Murray, “because pitchers who expected to be hit with a cork with a string on it, suddenly found an 88-millimeter howitzer opening up on them.” Within a few months after the nickname’s introduction, you could not read a word about Wynn without seeing it, and the same was true five decades later. Wynn eventually embraced “Toy Cannon,” using it as the title of his memoir, and it remained an indelible part of his identity as a beloved Houston icon in his retirement years.

James Sherman Wynn was born on March 12, 1942, in Cincinnati. His father, Joseph Wynn, was a garbage man. “When they came up with the newer, cleaner, term ‘sanitation worker,’” said Wynn, “I still called him a garbage man because that’s what he was doing and there is no shame in that work at all. If it weren’t for people like my dad, people who do the really essential work that has to be done, our cities would stink to high heaven and slow down to a dead stop.” Maude Wynn was a “stay-at-home mom,” who later worked outside the house as her seven children grew more independent. Jim was the oldest child raised in a tight, traditional, religious home.

Joseph had played semipro ball in Cincinnati, and coached young Jimmy both informally and also in Little League. Small and compact even as a kid, Wynn always surprised people with his strength and power. “My father made me the kind of hitter I am,” said Wynn in midcareer. “I was a shortstop when I was a boy growing up in Cincinnati and my father saw me as an Ernie Banks type – a good fielder who could hit home runs. He threw baseball after baseball at me, and when he got tired he took me out to a place near the airport where they had pitching machines. I developed the timing and the strong hands and wrists you need to hit homers.”

Wynn grew up a few blocks from Crosley Field, the home of the Cincinnati Reds, and long remembered watching some of the Reds players walking past his house on their way to or from the ballpark. At Robert A. Taft High School he played baseball, basketball, and football, and ran cross-country. Several high-school teammates went on to careers in professional sports, including Walter Johnson, who played defensive tackle for 13 years in the NFL. The Reds tried to sign Wynn after he graduated from high school in 1960, but his mother insisted that he instead attend Central State University in Wilberforce, about an hour away. He spent less than two years there, finding time to play both basketball and baseball, before signing with Reds in early 1962, just before his 20th birthday.

Wynn spent the 1962 season with Tampa of the Class D Florida State League. Mainly a third baseman, the 20-year-old hit .290 with 14 home runs while playing all of his team’s 120 games. He also drew 113 walks – Wynn’s ability to reach base was an underappreciated skill in the 1960s, but one that would provide great value to his teams over the years. Wynn recalled dealing with vicious racism in Florida that summer, though he credited his managers, Johnny Vander Meer and Hershell Freeman, with their humane treatment of him and his fellow black players. One of his black teammates was 19-year-old first baseman Lee May, who went on to an excellent major-league career and remained a good friend.

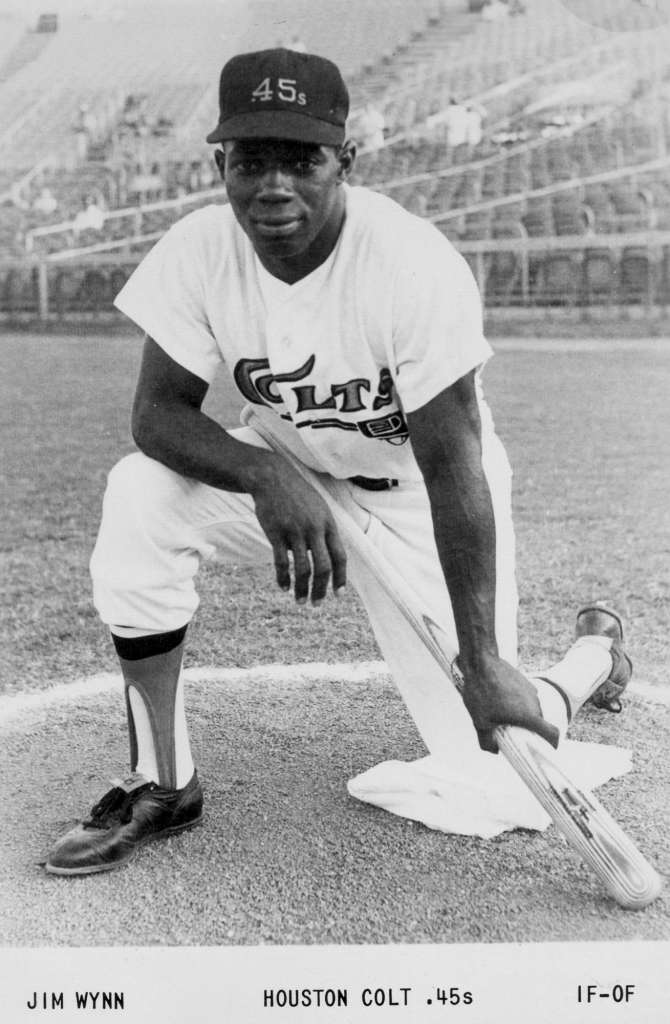

A baseball rule of the time allowed for “first-year” players to be drafted by other major-league teams if they were not placed on their organization’s 40-man roster. Accordingly, in November 1962 the Houston Colt .45s drafted Wynn from the Reds. This was quite a shock for a 20-year-old kid fresh off his first (excellent) professional season, but Wynn soon saw the advantages. The Astros had just finished their first season, and there would be far less competition for big-league jobs than there would be with the established Reds. Wynn started the 1963 season at Double-A San Antonio, where he played both shortstop and third base and batted .288 with 16 homers and 11 triples. By July he was in the major leagues.

He made his big-league debut on July 10 against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field, playing shortstop and managing a single off Bob Friend in a 2-0 victory. He hit his first home run off the New York Mets’ Don Rowe at the Polo Grounds on July 14, and his second off the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Don Drysdale on August 2 at Colt Stadium. He played nearly every day after his recall, batting .244 with four home runs. On September 27 he took part in a bit of history when the Colts fielded an all-rookie starting lineup, which included fellow call-ups Joe Morgan, Rusty Staub, Sonny Jackson, and Jerry Grote. More importantly, on July 23 manager Harry Craft started Wynn in center field for the first time, a position of great need for the club, and one Wynn would come to own.

In 1964 Wynn started for the Colts on opening day in center field, but a batting slump got him sent down to Triple-A Oklahoma City in June. He hit well there (.273 and 10 home runs) and was back in Houston in September. He batted just .224 in 67 major-league games that season. But his minor-league days had come to an end.

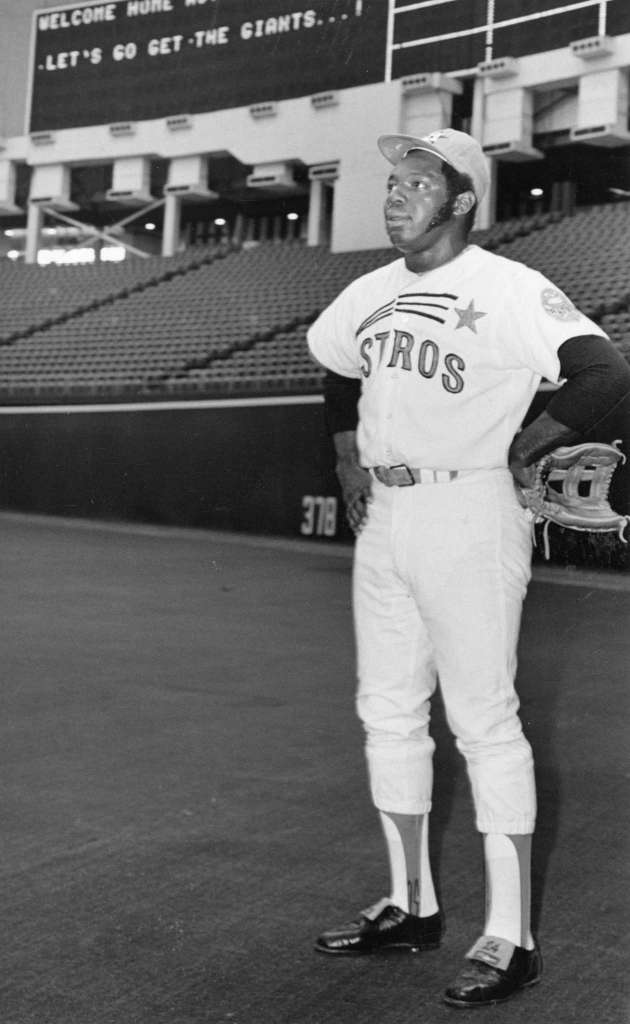

The big baseball news in Houston for 1965 was the opening of the Astrodome, the first indoor stadium used for baseball. The Colt .45s were rechristened the Astros, and Wynn broke through with his first star season. Playing 157 games, batting mainly third in the order, Wynn hit .275 with 22 home runs. He had 84 walks and stole 43 bases (in 47 attempts). Wynn hit well despite his cavernous home park, batting .305 with 15 home runs on the road, against just .247 and 7 home runs at home. People began to compare him, cautiously, to a center fielder in San Francisco who also wore number 24. “Men will die waiting for another Willie Mays to come along,” said one writer, “and Wynn isn’t the one they’re waiting for. But he’s only 24, and he can do everything nicely. For a few years after Willie packs it in, Wynn may be the not-too-inferior substitute.” How did such a relatively small man hit the ball so hard and so far? “I attack the ball,” Wynn said. “It’s the only way to hit.”

The Astros had two other breakthrough stars in 1965 – Morgan and Staub – but little else, and spent the first several years of their existence well behind the league leaders. The club started well in 1966 – they were 45-40 at the All-Star break – but a poor second half dropped them to eighth place. Wynn played well for four months (.256 with 18 home runs), before a terrible injury ended his season. Playing at Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium on August 1, Wynn crashed into the center-field wall chasing a drive by Dick Allen, breaking both his left wrist and elbow. Allen ended up with a game-ending inside-the-park home run on the play.

Wynn came back strong in 1967, crushing 37 home runs (second in the NL to Henry Aaron’s 39), and driving in 107 (fourth in the NL). These were big numbers for the era, and are especially impressive for someone playing half their games in the Astrodome; in fact, he led the NL with 22 home runs in road games. He set team records for both homers and RBIs, and his home-run mark would last until 1994. His batting average was just .249, but his on-base skills gave him a fine .331 on-base-percentage, well above the NL’s .310. He was selected to play in his first All-Star Game, getting a pinch single off the Yankees’ Al Downing in the NL’s 2-1 victory in Anaheim.

On June 15, against the Giants, Wynn became the first player to hit three home runs in the pitcher-friendly Astrodome, each one traveling over 400 feet. He hit one off the Budweiser sign behind the left-field bleachers in St. Louis’s Busch Stadium; he blasted one to the left of the flagpole in dead center in Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, over the 457-foot sign; and he belted another over the 45-foot-high scoreboard in Crosley Field that bounced onto a freeway. “Observers of tape measure home runs, unfortunately, do not have a record for preciseness,” observed one writer. “But it is generally agreed that Jim Wynn hits a ball about as far as it can go.” Wynn was less impressed, observing only, “I’m just swingin’ the bat and lettin’ wood meet horsehide.”

The 1968 season marked the height of the pitchers’ era, a year when run-scoring dropped to its lowest levels in 60 years. Wynn’s power numbers fell off to 26 home runs and 67 RBIs, though he again led the league in home runs on the road, with 17. Wynn was the only Astro with more than six home runs, and he hit nine of the 22 home runs his team hit in the Astrodome. He raised his batting average to .269, and his 90 walks led to a .376 on-base-percentage that was third best in the league. The Astros also finished in tenth (last) place for the first time, though their record of 72-90 was tied for the best in their seven-year existence.

Before the 1968 season the Astros brass decided to shift Wynn to left field and play Ron Davis in center, unsettling the incumbent. “The center fielder has the most responsibility,” said Wynn. “I like the responsibility.” Despite great speed, Wynn was never a great outfielder, and Davis was considered a big defensive upgrade. More than that, Wynn was often accused of playing nonchalantly – manager Grady Hatton had fined or benched him at least twice.

In early June 1968, Hatton was replaced by Harry Walker, who had been serving as the club’s batting coach. On June 15 Davis was hitting just .212 when he was traded to the Cardinals. Wynn returned to center field, though Walker would occasionally move Dick Simpson to center and Wynn to left later in the season. Wynn was benched in August by Walker for indifferent play. “Jim draws the salary of a big-league star and he has to produce like one,” said the new manager.

Walker had won a batting title in 1947 by hitting a lot of opposite-field singles, and did not approve of Wynn’s free-swinging batting style. Wynn had led the league with 137 strikeouts in 1967, and Walker believed that he was doing it all wrong. “He kept telling me I’d hit .300 if I just choked up on the bat, went to the opposite field and concentrated on average. No way. My swing was already grooved. I didn’t get all those home runs being a Punch-and-Judy hitter. I guess when you’re short, managers have a tendency to mess with you more.” The two barely held their animosity. Walker had similar problems with Joe Morgan – another small man with great speed who was underrated as an all-around offensive player because his batting average did not adequately reflect his contributions. Walker wanted Morgan to hit the ball on the ground and use his speed to get more singles. Like Wynn, Morgan rebelled.

In his 1993 memoir, Morgan unequivocally calls Walker a racist, believing that the manager thought that the blacks on the team were incapable of thinking for themselves, and that Walker would not treat them as adults. Wynn, in his 2010 memoir, agrees with Morgan, though he mostly focuses on Walker’s insistence that Wynn change the way he hit. “Harry took things into his own hands, where he tried to change me from being what I was to what he wanted me to be. I couldn’t do that. I rebelled; I rebelled a great deal. There was no name-calling or anything like that; it was just me doing what I wanted to do and not what he wanted me to do.” In fact, players like Morgan and Wynn – who derived most of their offensive value from walking and hitting with power at the expense of batting average – were undervalued by most everyone until a generation after they played.

Wynn enjoyed another excellent season in 1969, with 33 home runs and 87 RBIs. Most remarkably, he drew a league-leading 148 walks (tying the existing league record), leading to a .436 on-base-percentage. “Jim never sees a fastball anymore,” said Morgan at the time. “They throw him breaking balls down and away all the time. If we had someone who could hit even 15 home runs batting fourth, the pitchers would have to give Jim at least one pitch to hit.” The Astros’ most frequent cleanup hitter was Doug Rader, who hit 11 home runs and batted .246. Harry Walker generally chose not to talk about Wynn’s home runs. “If he hits a home run that goes 450 feet and we all start to talk about it, then he’ll start to think that he should try to hit a 470-foot home run,” said the manager. “When he tries to hit that 470-foot home run, he won’t hit the ball 400 feet.”

One of Wynn’s unique characteristics was an ever-present toothpick that he put in his mouth before a game, rolled around with his tongue and teeth for a few hours, and discarded when the game ended. “Some pitchers tell me they’re going to knock the toothpick out of my mouth when I come to bat,” he said, “but no one’s done it yet and no one’s going to do it, either.” Toothpicks and all, Wynn had another excellent season in 1970, with 27 home runs, 88 RBIs, and 106 walks.

Wynn had married Ruth Mixon in December 1964, and the couple had two children (Kimberly and Jimmy Jr.). Wynn acknowledged that it was not a happy marriage and that he was not a good husband. On December 21, 1970, their sixth wedding anniversary, a fight escalated enough that Wynn grabbed an unloaded shotgun, and Ruth stabbed Wynn in the stomach with a kitchen knife. Wynn later downplayed the severity of the injury, but he did undergo abdominal surgery. The Wynns divorced soon after the incident, and Wynn missed his children terribly. Perhaps not surprisingly, he stumbled mightily on the field in 1971 (.203 with seven home runs), a disappointment he later attributed indirectly to his off-field problems. “I can honestly say that I never before felt less likely playing ball or doing anything good for myself than I did that year.”

Meanwhile, his problems with Walker also grew worse. “I had given up some time earlier on doing anything to comply with a request or order from Harry, but now I was just flat-out ignoring him.”The low point might have been July 17 in a game against the Mets. In the bottom of the first in a 1-1 game, Wynn batted against Nolan Ryan with one out and the bases loaded. Ryan had already walked three in the inning, and the count quickly reached 3-0. Ignoring the “take” sign, Wynn popped up to second base. After the game, an Astro victory, Walker called Wynn into his office and told him he was being fined. Wynn stormed out, and the two began shouting at each other while Wynn threw stuff around the clubhouse. Wynn also threatened to hit Houston Chronicle writer John Wilson if the incident appeared in the paper, which it did the next day. Wilson quoted Joe Morgan saying, “Wynn was wrong for swinging at the pitch and deserved a fine.” Wynn himself allowed, “I knew I was wrong when I did it. Other than that I have nothing to say.”

Although many assumed the Astros would fire Walker or trade Wynn after the 1971 season, they chose to keep both but trade Morgan, who Walker believed was a bad influence on Wynn. Surprisingly, the Astros improved to 84-69 in 1972, due to a suddenly potent offense. Besides Lee May, the key newcomer from the Morgan trade, the Astros enjoyed a breakthrough season from Cesar Cedeno (whose emergence had moved Wynn to right field) and a nice comeback from Wynn (.273, 24 homers, 90 RBIs, 103 walks, and a career-high 117 runs). “I have never been this happy,” he said that summer. “Never! The Houston Astros of 1972 are what Jim Wynn always hoped would happen to him sometime during his career.” As for Walker, he seemed to have given up trying to shape his team. “A lot of them resent teaching,” he said. “I try to avoid talking to my players as much as possible. Players aren’t like they were in the old days.” Somewhat surprisingly, given the Astros’ progress, Walker was fired in late August and replaced by Leo Durocher.

The new manager did not try to change Wynn’s swing, but he did move him to leadoff in the batting order to take advantage of his on-base skills. Wynn thought of himself as an RBI guy, and bristled at the move. Coincidence or not, Wynn’s average dropped to .220 in 1973, though his 20 home runs and 91 walks still provided value to the club.

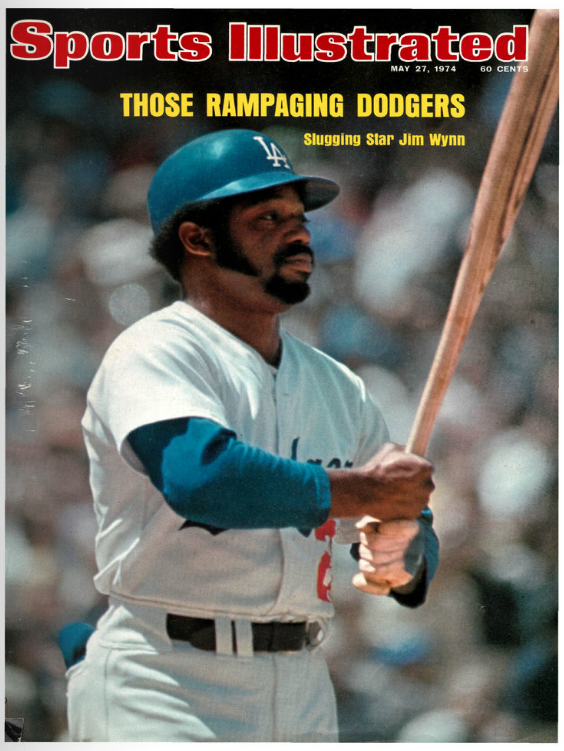

In December 1973 Wynn was traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers for pitcher Claude Osteen and a minor leaguer. According to Sports Illustrated, Wynn’s new manager, Walter Alston, “advised Wynn that he could bat third, play center field, swing at the ball any way he damn well pleased as long as he hit it from time to time, and have complete freedom on the bases.” Wynn was thrilled. His new batting coach was Dixie Walker, Harry’s brother. “He came up to me and told me he knew I’d had some problems with his brother,” Wynn said. “He told me I needn’t worry about him. I appreciated that and I told him the problems I had with Harry had been greatly exaggerated.” The odd couple began golfing together. And Wynn became instantly popular in LA, whose fans turned part of the left-center-field bleachers into “Cannon Country.”

The 32-year-old Wynn had one of his best and happiest years in 1974, batting .271 with 32 home runs (setting a new LA Dodger record) and 108 RBIs, while drawing 108 walks. He started the All-Star Game in center field, finishing 1-for-3 (a single off Luis Tiant). More importantly, the Dodgers had a spectacular season, finishing 102-60 to beat a great Cincinnati Reds for the division title. Wynn, who had hurt himself late in the season, hit just .200 in the NLCS (the Dodgers defeating the Pirates, 3-1) and .188 in the five-game World Series loss to Oakland. His postseason highlight was a long ninth-inning home run in Game One of the World Series off Rollie Fingers, cutting the A’s lead to 3-2. The A’s closed out the victory two batters later. After the season, The Sporting News named Wynn its National League Comeback Player of the Year.

Wynn had a tremendous start to the 1975 season, hitting .270 with 14 home runs and 79 walks at the All-Star break. He started the game again, batting 1-for-2 with a home run off Vida Blue. He fell off terribly in the second half, and ended up hitting just .248 with 18 homers, though 110 walks. It was a very good season, just not what it looked like it would be. Perhaps sensing this slump was different, after the season the Dodgers dealt Wynn to the Atlanta Braves in a six-man trade that brought Dusty Baker to Los Angeles.

Wynn’s career wound down quickly after that. He hit .207 for the 1976 Braves, though with a league-leading 127 walks. After the season he was sold to the New York Yankees, for whom he hit just .143 in 30 games, and he finished that season with Milwaukee, hitting .197 in 36 games. His only 1977 home run was hit on Opening Day in Yankee Stadium off Milwaukee’s Bill Travers. It was the 291st of his career, and his last. Just 35 years old, he retired after drawing his release from the Brewers.

He had married his second wife, Joanne, in 1972, though they divorced at the end of his tenure with the Dodgers. With his career ended, Wynn settled in Los Angeles, taking a job with a beverage company mainly doing appearances. He also played a lot of golf. He made a brief comeback with Coahuila in the Mexican League in 1979 but realized quickly that he could not play anymore. In the early 1980s both of Jimmy’s parents passed away in Cincinnati. Wynn had remained close to them, and their loss was made doubly painful by his long separation from his own two children, still living in Houston with their mother, Ruth. In 1985 Wynn sold his house and found an apartment in Houston.

In his memoir, Wynn details the gradual repairing of his relationships with Kimberly (born in 1965) and Jimmy Jr. (1967). Wynn admits with regret that Ruth’s early death from cancer a few years later removed one of the barriers to reconciliation. In 2010 he was able to write, “My love for them is flesh-and-blood unconditional,” a love he had felt from his own father.

After a few years working as a bartender in a black social club, in 1988 Wynn went to work with the Astros in community relations. Over the next 25-plus years he continued this role, speaking with kids and adults throughout the city on the virtues of hard work, staying in school, staying away from drugs. He got involved with the Major League Players Alumni Association, eventually joining their board. He made one attempt to get back into uniform – serving as hitting coach for the New Orleans Zephyrs 1997 – but realized that the travel and associated hassles were no longer for him. He was inducted into the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame in 1992, and a dozen years later the group began giving the Toy Cannon Award for exceptional community service, giving the first award to Wynn.

One evening in 1992 Wynn met a woman named Marie at a nightclub and the two hit it off. In 2000, having dated for eight years, they were on a trip to Hawaii with a baseball alumni group when they were coaxed into an essentially spur-of-the-moment wedding. After getting a license, a proper official, an impressive group of best men (including Gaylord Perry, Mudcat Grant, Steve Carlton, Tommy Davis, and Ferguson Jenkins) and a maid of honor (Grant’s wife Trudy), the two were married in their shorts and Hawaiian shirts.

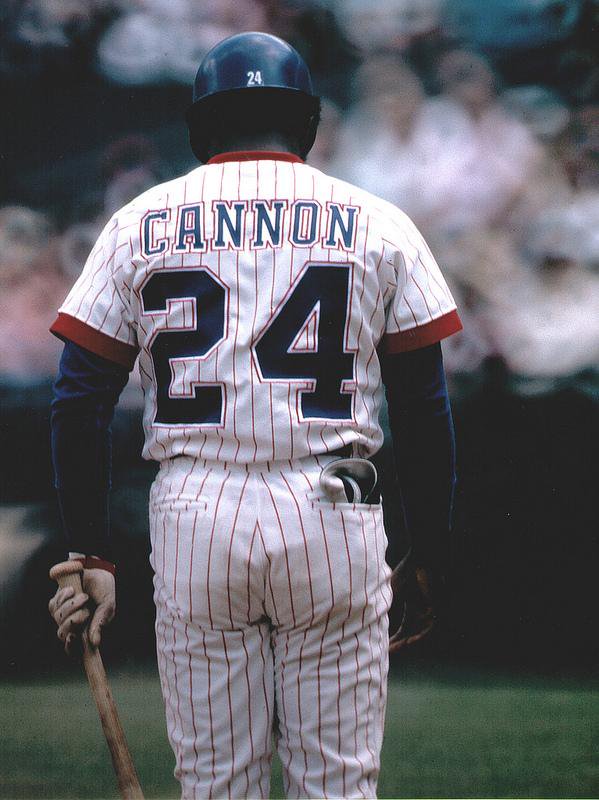

In 2005 the Astros permanently retired Wynn’s number 24 at the new Minute Maid Park. “Anytime you get your number retired, it’s almost like getting into the Hall of Fame,” said Wynn. In 2011 the Astros opened the Jimmy Wynn Training Center in Houston, a baseball facility for urban youth. He also began working in television on the Astros postgame shows.

Wynn’s path was not always easy or smooth, but his memoir is filled with self-awareness (for his past mistakes), forgiveness, and appreciation for nearly everyone he ever met. By 2014 Wynn seemed blissfully happy with his family, his city, and his life. After spending 11 occasionally rocky years in Houston as a young man, the love affair between the city and their “Toy Cannon” was stronger than ever.