From MLB.com By Todd Zolecki

December 7, 2020

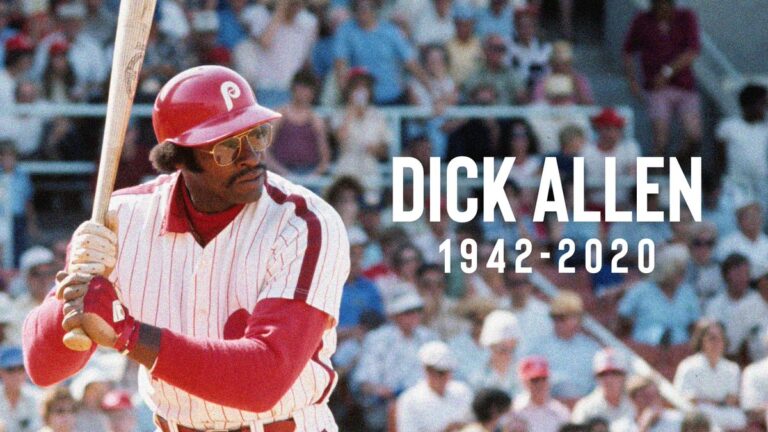

PHILADELPHIA — Dick Allen long ago captured the hearts and minds of a generation of Phillies fans.

It started in 1964, when Allen won the National League Rookie of the Year Award and finished seventh for NL MVP. He became an instant Philadelphia folk hero, carrying a massive 40-ounce bat to home plate, taking aggressive swings at the baseball and launching majestic home runs into the bleachers.

He was larger than life. He was one of the game’s greatest players over his 15-year Major League career. He should be regarded as one of the greatest players in baseball history.

Allen died on Monday at age 78 in Wampum, Pa., the town where he was born in 1942. His impact on Philadelphia and baseball will not be forgotten.

“The Phillies are heartbroken over the passing today of our dear friend and co-worker, Dick Allen,” the Phillies said in a statement. “Dick will be remembered as not just one of the greatest and most popular players in our franchise’s history, but also as a courageous warrior who had to overcome far too many obstacles to reach the level he did.

“Dick’s iconic status will resonate for generations of baseball fans to come as one of the all-time greats to play America’s Pastime. He is now reunited with his beloved daughter, Terri. The Phillies extend their condolences to Dick’s widow, Willa, his family, friends and all his fans from coast to coast.”

Allen had a Hall of Fame career, but the honor eluded him since he played his final game in the big leagues in 1977. He does not have a bronze plaque in Cooperstown, N.Y., because he had been labeled a controversial figure during his playing career. Reporters deemed him too surly, too opinionated. He fought teammates. He sometimes showed up late to the ballpark. But Allen battled racists and racism throughout his career. He spoke up and fought back, which was not welcomed. It cost him the adulation and recognition he deserved.

“I wonder how good I could have been,” Allen wrote in his memoir ‘Crash.’ “It could have been a joy, a celebration. Instead, I played angry. In baseball, if a couple things go wrong for you, and those things get misperceived, or distorted, you get a label. I was labeled an outlaw, and after a while that’s what I became.”

But perspectives change and people started to view Allen’s career much differently over the past few years. They started to realize what an incredible player he was. They started to realize he had been treated unfairly.

The Phillies did something about it and retired Allen’s No. 15 in September because they realized one of the greatest players in baseball history needed to be recognized, whether or not the Hall of Fame did. (The Phillies previously had an unofficial policy of retiring numbers of players only in Cooperstown). Hall of Fame third baseman Mike Schmidt and managing partner John Middleton spoke during the retirement ceremony about Allen’s career and some of the controversy that surrounded it.

“Dick did the wrong thing; he became the best player on his team,” Schmidt said. “He became the star of the team. He was a sensitive Black man who refused to be treated as a second-class citizen.”

Added Middleton: “It makes the extraordinary achievement even more special when you consider the circumstances, the conditions under which he had to live and perform.”

Ironically, Allen would have learned on Monday if he finally made the Hall. The Golden Days Committee planned to vote again on Sunday at the Winter Meetings, but they were cancelled because of the pandemic. The Hall of Fame then postponed the committee’s vote until next year because it claimed it could not hold those discussions and votes virtually.

Allen fell one vote short the last time the committee voted in 2014. There is reason to believe that Allen would have made it this time.

Look at Allen’s career numbers played mostly in a pitcher’s era. Look at his accomplishments. The first baseman who came up playing third base slashed .292/.378/.534 with 351 home runs, 1,119 RBIs, a .912 OPS and a 156 OPS+ during time spent with the Phillies, Cardinals, Dodgers, White Sox and A’s from 1963-77. His OPS+ is tied for sixth all time among right-handed hitters in the modern era. He won the ’72 American League MVP Award and the ’64 NL Rookie of the Year Award. He made seven All-Star teams, including three with the Phillies. He earned MVP Award votes in six other seasons.

From 1964-74, Allen posted a 58.3 WAR, according to Baseball Reference. It tied Willie Mays for sixth place among position players in that 11-year span, behind Hank Aaron (68.8), Carl Yastrzemski (68.1), Roberto Clemente (64.7), Ron Santo (60.1) and Brooks Robinson (59.3). Pete Rose (58.0), Frank Robinson (55.4) and Joe Morgan (54.0) rounded out the top 10.

Allen led his league in OPS four times, slugging three times, on-base percentage and homers twice each, and RBIs, runs and walks once each. Despite that, he was traded five times. One of those deals, from the Dodgers to the White Sox in December 1971, set up his MVP Award-winning campaign. He returned to the Phillies in a trade in May ’75, after he refused to report to the Braves following a trade and announced his retirement despite having just won his second home run title in ’74.

“He’s the greatest player I’ve ever seen play in my life,” Hall of Fame closer Goose Gossage told USA Today in 2014. “He had the most amazing season (1972) I’ve ever seen. He’s the smartest baseball man I’ve ever been around in my life. He taught me how to pitch from a hitter’s perspective, and taught me how to play the game, and how to play the game right. There’s no telling the numbers this guy could have put up if all he worried about was stats.

“The guy belongs in the Hall of Fame.”

Todd Zolecki has covered the Phillies since 2003, and for MLB.com since 2009. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook .