Similar Posts

On this day… Mr. Cub Slugs #500

On this day in 1970, Chicago Cubs first baseman Ernie Banks swung his way into Major League Baseball history with his 500th home run. The historic moment came when Mr. Cub launched a solo shot into left center field in the second inning against Atlanta Braves righty, Pat Jarvis. The game featured six future Hall of Famers, four on the…

DA15 Instagram Post – Fisk to Chicago

DA15 Instagram Post: OTD in 1981, Carlton Fisk changed his “Sox” and flipped his number #WhiteSox

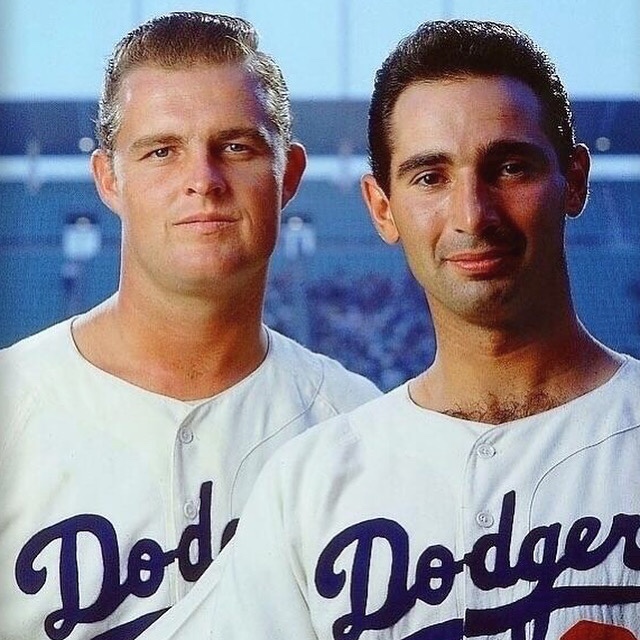

DA15 Instapost: Koufax & Drysdale Return

OTD in 1966 – #Dodgers Don Drysdale & Sandy Koufax end their dual 32 day holdout. Koufax signs for $120K; Drysdale settles for $105K.

On This Day… Big League Debut

On this day in 1963… 21 year old Richard Anthony Allen made his major league debut for the Philadelphia Phillies. Following Little Rock’s (AAA) International League season in which he led the team in hitting (.290), led the league in home runs (33), runs batted in (97), triples (12) AND broke the color barrier as…

Celebrating Jackie Robinson Day 2020

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson became the first African-American player in modern Major League Baseball when he stepped onto Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field with the Dodgers. Today, we celebrate an American hero and civil rights icon whose legacy endures on and off the field. Check out our Wallpaper Page

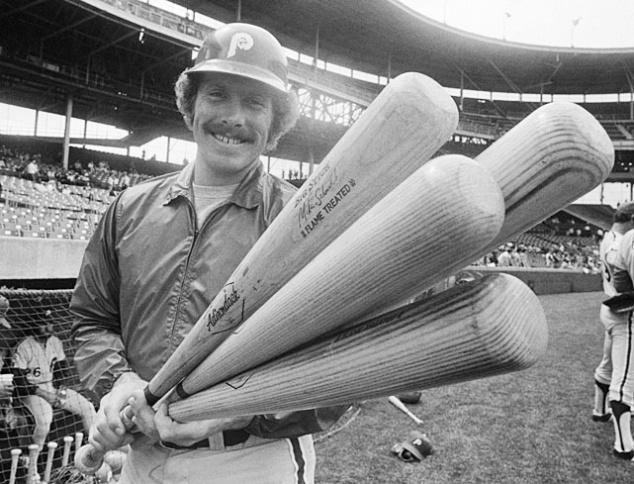

Schmidt Hits 4 at Wrigley

On this day in 1976… Michael Jack Schmidt, the greatest third baseman in baseball history, blasted four home runs in Chicago to lead the Phillies to an impressive comeback win against the Cubs. The below is an original article from the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) written by our friend Rich D’Ambrosio. April 17,…